Immunotherapy, also called biologic therapy, is a relatively new form of cancer treatment that began gaining recognition in the past few decades, as it uses the body’s natural immune system to fight illnesses, such as cancer. Our immune system is what helps the body fight against infections and diseases. Like many other forms of treatment, immunotherapy is complex and not all immunotherapies work the same.

WebMD notes that some immunotherapies are designed to boost the immune system, while others “try to teach it to attack very specific types of cells found in tumors.” Of course, each one also has its pros and cons. To get better informed on the topic of immunotherapy, let’s take a deeper look into each of the different types…

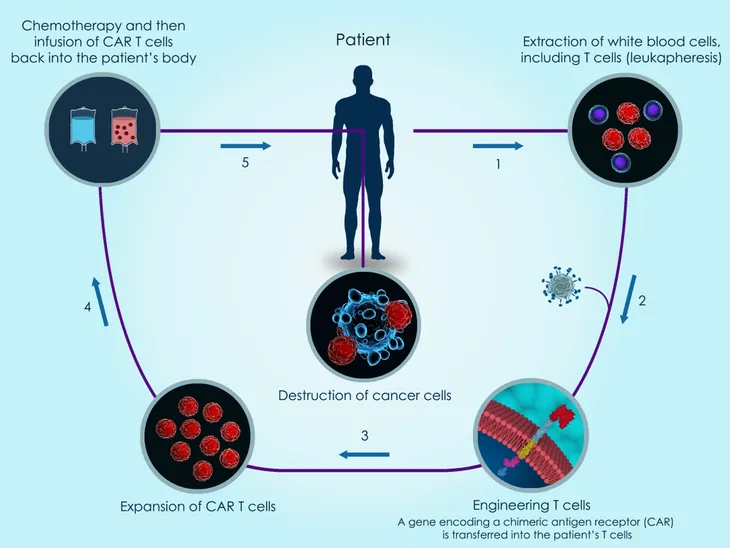

Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy is also known as adoptive cell transfer (ACT) therapy. Currently, this form of immunotherapy is available as two different types of medication: tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) and axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta). According to WebMD, tisagenlecleucel is “used to treat children and adults up to age 25 with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) whose cancer didn’t respond to chemotherapy or who had the disease come back two or more times after treatment.” Axicabtagene ciloleucel, on the other hand, is for adults who have a large B-cell lymphoma, such as non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Similar to tisagenlecleucel, this immunotherapy is only used if the cancer didn’t respond to other treatments or if the cancer has come back after using other treatments.

T-cells are a type of white blood cell that the immune system uses to fight off diseases. “Antigens are foreign substances your immune system targets. When your immune system senses antigens in your body, it releases T-cells as self-defense,” writes the source. CAR T-cell therapy works to reprogram the body to use its T-cells to attack the cancer. The body will first go through a process called leukapheresis, which takes a few hours. Then, the doctors will “take blood out of your body, separate some T-cells from other white blood cells, then put your blood back in.” Technicians will then add in CARs to the T-cells so they are better programmed to attack the cancer cells. This reprogramming will take a few weeks. Before the cells are put back into the body, the patient might need to undergo chemotherapy just to decrease any other types of immune cells in the body. “This helps clear the path for the T-cells to do their work. Once the CAR T-cells are ready, your doctor puts them into your bloodstream,” writes WebMD. The CAR T-cells will multiply and attack the cancer cells.

This type of immunotherapy will result in some serious side effects, such as a higher fever, low blood pressure, confusion, headaches, seizures and a weak immune system, low blood count, or severe infection, says WebMD.

TCR Therapy

T-cell receptor (TCR) therapy is similar to CAR T-cell therapy because it’s another form of ACT therapy that is used to fight cancer. Similar to CAR T-cell therapy, doctors will remove blood from the body and reprogram the white blood cells so that they can find the cancer cells more easily. “But TCRs tell the T-cells to look for tiny bits of specific antigens inside your cancer cells,” writes WebMD. In a similar process to CAR T-cell therapy, T-cells are taken from the blood and reprogrammed. After the patient undergoes a round of chemotherapy, the engineered T-cells are put back into the body, explains the source.

WebMD notes that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) hasn’t actually approved any TCR therapies. Some are still in the testing stage, mainly on people who have certain types of synovial sarcoma (a soft tissue cancer) and metastatic melanoma. The source goes on to state that the results so far are mixed. It has worked for some people, but only for a few months. In these trials, people had different reactions to the immunotherapy. Some people experienced no side effects, while others had mild or moderate symptoms, including “diarrhea, fevers, fatigue, rashes, and nausea,” says WebMD. There were also more serious reactions, such as dehydration, high fever, and graft-versus-host disease.

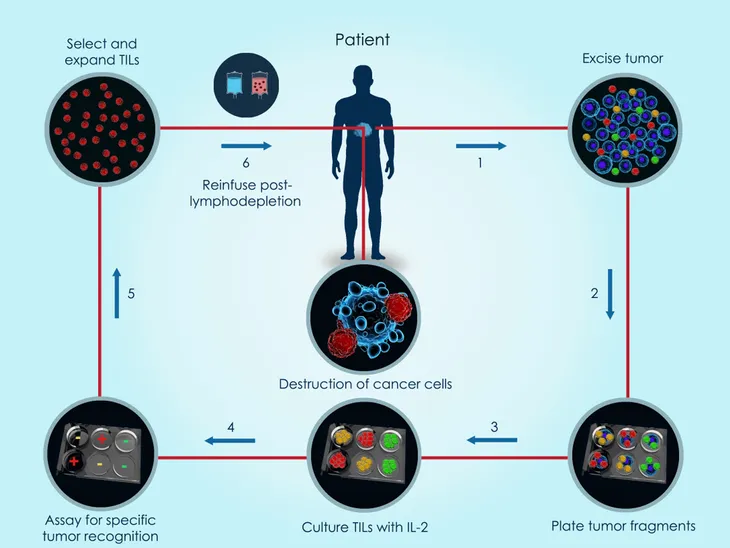

TIL Therapy

The third type of ACT therapy we will discuss here is tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL). Unlike the previous two immunotherapies we just discussed, TIL therapy doesn’t take blood and reprogram it in a lab. This therapy works by using cells made by the body’s immune system. “If these cells have gotten inside the cancer cells, it’s a sign that your body isn’t trying to fight the cancer on its own,” says WebMD.

During the process of TIL therapy, doctors will take TILs from the tumor tissue and grow them in a lab. “They then turn up their cancer-fighting ability by adding proteins called cytokines,” writes the source. “These proteins help your TILs find and destroy cancer cells.” Once a patient has gone through chemotherapy to lower the number of T-cells, the TILs are put into the bloodstream in a single dose with the hope that the “turned up” white blood cells are now better equip to fight off the tumor.

TIL therapy is currently being tested on patients with colorectal, kidney, ovarian and skin cancers (such as melanoma). WebMD notes that the early results are good, but the biggest challenge with this form of therapy is that it’s hard to retrieve TILs from a patient.

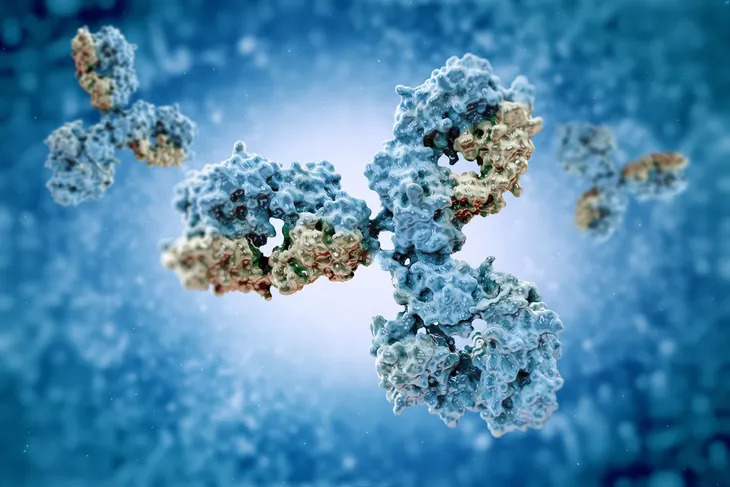

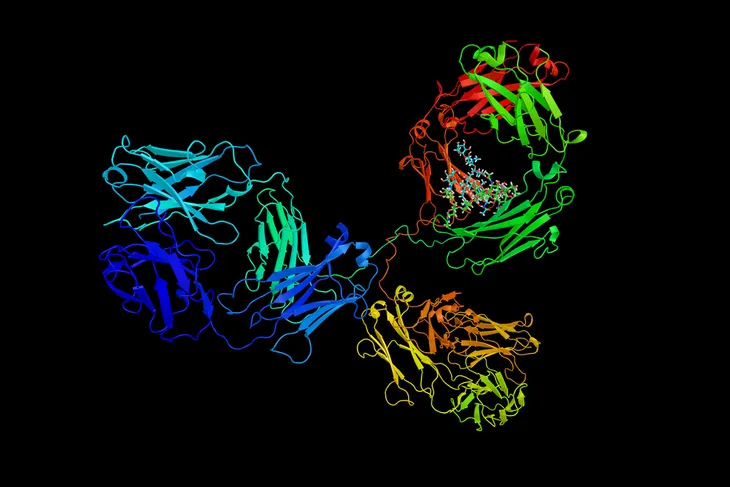

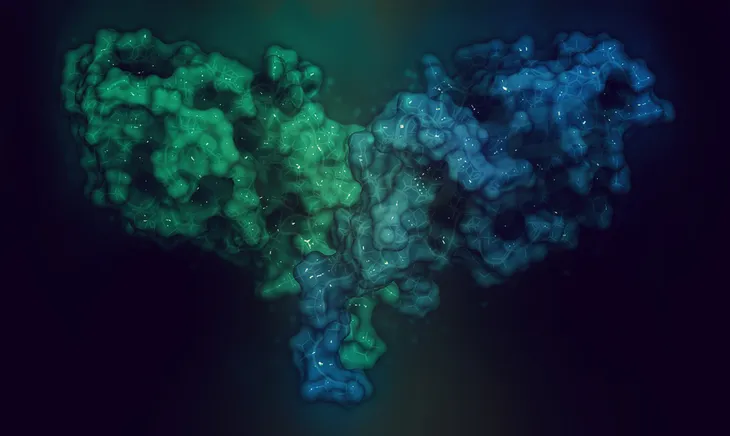

Monoclonal Antibodies

To understand monoclonal antibodies, we first must know what an antibody is. WebMD explains that an antibody is a molecule that flags proteins in the body as invaders. “It then recruits other parts of your immune system to destroy any cells that contain those proteins,” says the source. Science has come a long way and researchers are now able to make their own antibodies in a lab. These man-made antibodies are called monoclonal antibodies. The most commonly used ones for immunotherapy are naked monoclonal antibodies, conjugated monoclonal antibodies, and bispecific monoclonal antibodies.

Naked Monoclonal Antibodies

According to WebMD, naked monoclonal antibodies are the most common type of immunotherapy for cancer treatment because they don’t have anything attached to them. “They tell your immune system to attack cancer cells or block proteins within tumors that help the cancer grow,” explains the source.

Conjugated Monoclonal Antibodies

This antibody has a chemotherapy drug, also known as a radioactive particle, attached to them. What makes these antibodies different is how they attach to the cancer cells. They will attach themselves directly to the cell. “That means they deliver these drugs where they’re needed the most,” says WebMD. Conjugated monoclonal antibodies might be used in tandem with chemotherapy, because they tend to help these other treatments work better. “This lowers side effects and helps treatments like chemotherapy and radiation work their best,” explains the source.

Bispecific Monoclonal Antibodies

Bispecific monoclonal antibodies are designed by researchers to bind two different proteins at once. Some of these antibodies work by binding to both a cancer cell and an immune system cell to help the immune system to attack the cancer better.

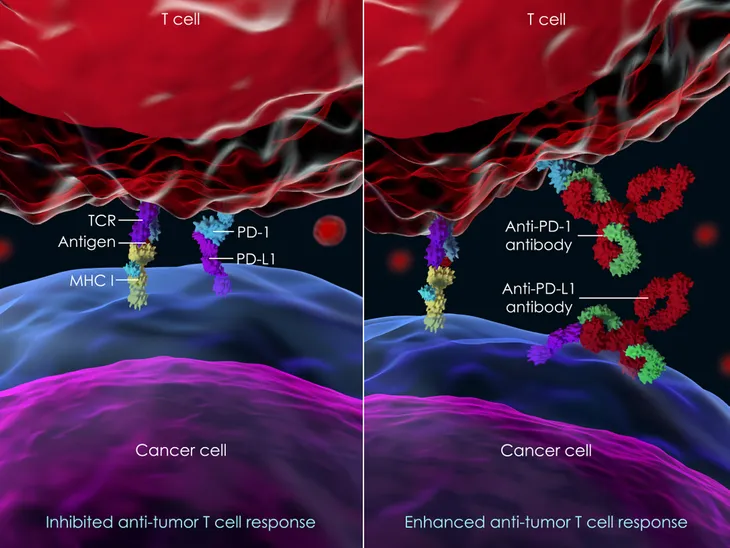

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

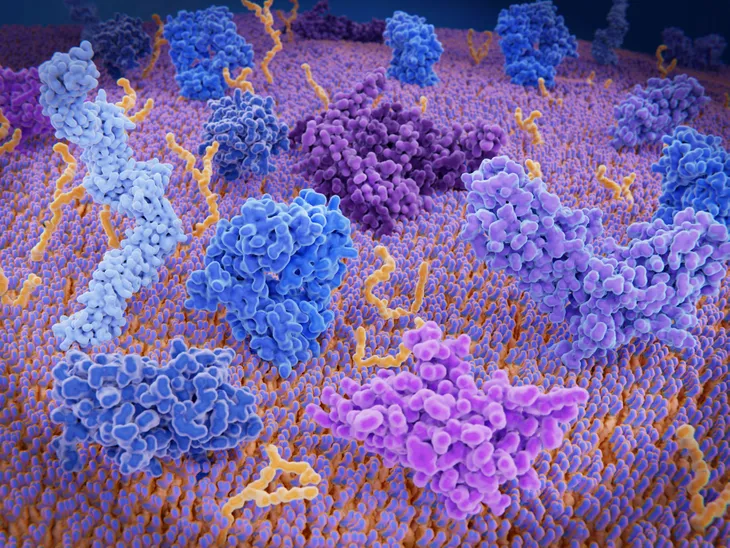

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are just like any other checkpoint. A place where things come to a halt, so the situation can be evaluated. For the immune system to remain healthy, it has to stop invading molecules, such as bacteria and viruses. With that being said, it also has to know how to decipher which cells to attack and which ones should be left alone. To help with this process, the immune system has molecular breaks called checkpoints, says WebMD. “Cancer cells sometimes take advantage of them by turning them on or off so they can hide,” writes the source. This is where immune checkpoint inhibitors come in handy. These drugs work to help these breaks do their job.

There are two different kinds of immune checkpoint inhibitors: PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors and CTLA-4 inhibitors. Both of these drugs can cause a number of side effects, since they are designed to rev up the immune system. Possible side effects including “fatigue, cough, nausea, loss of appetite, and rash, as well as problems in the lungs, kidneys, intestines, liver or other organs,” have been reported.

PD-1 or PD-L1 Inhibitors

These immune checkpoint inhibitors “target checkpoints called PD-1 or PD-L1 that are found on T-cells in your immune system,” writes WebMD. They are typically used to treat cancers like melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, kidney cancer, bladder cancer, head and neck cancers, stomach cancer, colorectal cancer, and Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

CTLA-4 Inhibitors

CTLA-4 inhibitors actually turn off the CTLA-4 checkpoint. This checkpoint is found on T-cells. WebMD informs that they are often used for melanoma, colorectal cancer, and other types of cancers.

Cancer Vaccines

We’re most familiar with vaccines created to fend off common viruses, such as the flu, but a vaccine can be anything that is created and put into the body to start an immune reaction, says WebMD. Cancer vaccines are created to spur the immune system to attack tumor cells. “They can be made of dead cancer cells, proteins or pieces of proteins from cancer cells, or immune system cells,” writes the source.

There are many different cancer vaccines that are being developed by researchers. The only approved cancer vaccine right now is sipuleucel-T (Provenge), which is used to treat advanced prostate cancer.

General Immunotherapies

There are other forms of immunotherapy that don’t necessarily target a tumor (unlike other forms of cancer treatment). These instead just work to boost the immune system, better equipping it to fight off cancer. WebMD explains that these general immunotherapies are divided into different classes of drugs. The first class of drug is interleukins, which are a type of cytokine, a “molecule produced by some immune cells to control the growth and activity of other immune cells,” writes the source. This class of drug has been approved to treat advanced kidney cancer and metastatic melanoma by using man-made interleukins.

The second class of drug is interferons, which are another type of cytokine that can change how our immune system works. Interferons are used to treat cancers, such as hairy cell leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, cutaneous (skin) T-cell lymphoma, kidney cancer, melanoma, and Kaposi sarcoma, says WebMD. The third class of drugs is known as colony stimulating factors, which work to strengthen the immune system by boosting the production of white blood cells in the bone marrow. The source explains that this works to help the body return back to normal after chemotherapy.

WebMD notes there are other drugs available, such as “imiquimod (Zyclara), lenalidomide (Revlimid), pomalidomide (Pomalyst), and thalidomide (Thalomid) to kick-start immune system reactions and are used to treat some cancers.”