If your dentist tells you that you may have a case of tooth resorption (also called root or dental resorption), you will probably look at them funny. That’s because it isn’t a term you hear very often, as the condition (involving the breakdown of mineralized tissue) is fairly uncommon among adults.

However, this condition can cause your tooth (or multiple teeth) to be eaten away from the inside out or vice versa— however with early detection, there are steps that can be taken to save the tooth. Let’s look at six facts about this relatively rare dental issue…

1. It Can be Symptom-Free

Root resorption (external in particular, but we’ll get to that) is often without any obvious red flags, unless the tooth has been visibly damaged by external factors, explains DentalCareMatters.com. In other words, you may not experience any pain and have no idea something is amiss (until your tooth has become loose). There’s also the “Pink Tooth of Mummery,” which we’ll detail later.

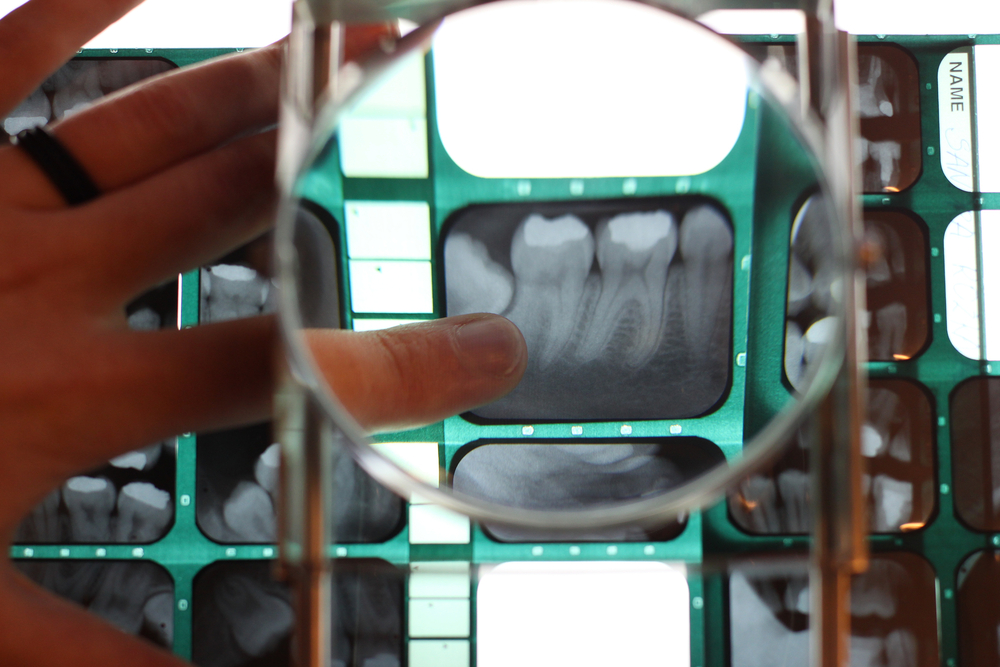

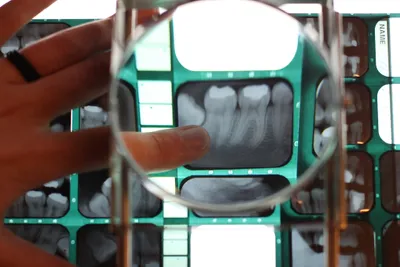

The dentist will usually only be able to detect the problem using a conventional x-ray. While there are some known triggers that can lead to resorption (we’ll get to those too), oftentimes the problem doesn’t seem to have any obvious root cause.

2. It Acts Like an Autoimmune Disease

A website called Simple Remedies explains that dental resorption occurs when your body perceives a foreign threat and attacks it—in this case, it happens to be a tooth. This is the same thing that occurs when you have an autoimmune disorder; your immune system turns against your own healthy cells.

In many cases, the tooth in question has been damaged, and “the damage can be so severe that the body starts to attack the healthy or intact tooth,” notes the source. This can cause the tooth to become loose as it weakens.

3. There are Two Main Types

Your dentist will identify which type of dental resorption you’re suffering from: internal or external. Neither is particularly positive, but internal seems to be the worse of the two, as it can destroy the tooth’s root without any warning.

External resorption begins from the outside and works its way in, but as mentioned before, you might not notice any signs of damage until your dentist takes a routine x-ray. It can also lead to the loss of the tooth from loosening, or your dentist may opt to extract it.

4. There are Root Causes

DearDoctor.com explains that “the exact nature of external cervical resorption isn’t fully understood,” but there are risk factors. For example, force on your teeth from braces (orthodontics) can cause tooth resorption to occur down the road, explains the source.

Other factors include an impact to the teeth that damages the periodontal ligament that attaches the tooth to the jawbone. If you grind your teeth, this can trigger the problem as well (ask your dentist about wearing a night guard). Some dental procedures and certain tooth bleaching methods have also been known to raise risks, it adds.

5. The Tooth can Be Saved

Simple Remedies notes the key in treating resorption is to act on it quickly. Some conventional methods can be used such as a root canal that drains the infected pulp and then fills and seals the cavity. If there’s an infection, the root canal treatment can be accompanied by the use of calcium hydroxide.

In some cases, the tooth may be beyond repair and need to be extracted and replace with a dental implant. There are also many cases where the resorption process is slow, and your dentist may even be able to reverse the damage from a long-term case—or choose to leave the tooth as it is if the damage isn’t progressing.

6. Internal Resorption Identified 200 Years Ago

A little history on this condition—the internal version in particular. A post on the U.S. National Library of Medicine notes the problem was first reported in 1830, and was later labeled the “Pink Tooth of Mummery” named after the anatomist James Howard Mummery.

This is because with internal resorption, there can sometimes be a telltale pink discoloration of the tooth’s crown. However, there’s ongoing research about internal resorption, as the dental community tries to pinpoint more exact causes (such as genetic factors).