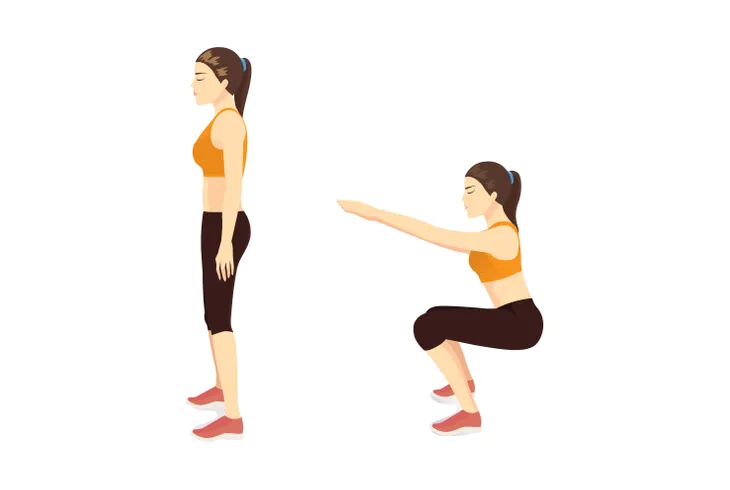

If you belong to a gym, you know there is no shortage of unsolicited exercise advice and you have probably heard it all—even if you didn’t ask for it. One exercise people need good quality advice on is squatting.

Although the exercise seems simple, there is actually a lot to performing a squat correctly and safely. Done incorrectly, squatting with load (e.g. a barbell) can lead to significant injury. Since the squat is one of the most effective exercises out there, this article will set the record straight on the dos and don’ts of squatting…

Worst: Arch Your Back

Arching your back or lifting your chest is often given as cue meant to remind you to keep your spine neutral, not flexed. Unfortunately, this cue can often lead exercisers to over-arch their back, causing increased pressure on their mid and lower back. Additionally, exercisers then tend to strain their neck backwards to compensate for the exaggerated arch in their back, leading to neck strain.

What you should do is focus on a neutral spine and keeping your neck relaxed by tucking in your chin slightly. If you have a friend snap a photo of you, you should notice a gentle curve from your mid to low back and your bum pushed back, not under. If you see your bum tucked under, this means you have posteriorly tilted your pelvis, , is a precursor to back injury. To practice, stand above a chair and think about reaching back towards the chair, bum first.

Worst: Suck in Your Core

Using your core muscles to support you throughout the squat is paramount to preventing injury. Activating your core muscles provides stabilization and support to the spine throughout the movement and prevents other muscles from taking on unnecessary load (such as muscles in your low back) and saves your spine. However, the common advice to pull your belly button towards your spine is more likely to cause, not prevent injury.

When you think about pulling your button towards your spine, you reduce the intra-abdominal pressure your core can create, which acts as a natural belt to your spine. Instead, think about creating pressure through your spine by pushing your stomach down and out slightly, as though you were preparing to take a punch. Then, maintain that pressure throughout the squat and don’t forget to breathe. Practice this technique with a bodyweight squat before progressing to weighted squats.

Worst: Deep Squats Will Ruin Your Knees and Back

Naysayers of the deep squat claim that this extended range of motion will destroy your knees and low back. This is a classic example of putting the cart before the horse. We cannot say an exercise will result in injury without understanding the technique and unique physical attributions of the person performing it.

Performed correctly, deep squats can be completely safe. However, not only does this demand greater attention paid to technique, it also requires the mobility and stability to work in that extended range of motion. In particular, sufficient range of motion through the hip joints, ankle joints, and core strength are needed. If these qualities are present, and there is no history of major knee or back injury, deep squats can be safe to perform. The better question is—what range of motion should you work in that respects your limitations and is best aligned with your goals?

Worst: Just Keep Adding More Weight

Squatting, especially under progressive loads, is extremely demanding on the body. While it is a very effective exercise in building full body strength, a squatting program should be designed that allows for adequate amounts of rest and works in a variety of range of motion, reps, and set schemes. It is not possible to add weight to your squat indefinitely, which is why prioritizing your program is the best way to guarantee consistent progress over the long term.

If you have been squatting the same barbell weight for several weeks, something should be tweaked. Change up your squat routine by trying some of the following: take a de-load week in which you squat at 60-percent of your normal weight for the same sets; switch to a heavier weight at lower reps and sets or lighter weight and greater sets, try box squats, pause squats, narrow squats or front squats; or work on single leg squat variations.

Worst: It’s Safer to Use the Smith Machine

If you’re new to squatting more than your body weight, there is a good chance someone has pointed you to the smith machine. At first glance, it might seem like a good way to remove the guesswork of proper form because the bar remains stuck in a certain bar path. However, unless you are a bodybuilder looking to use smith machine squats to build isolated hypertrophy, these machines are terrible for learning to squat.

The problem is that the technique that smith machine squats require is very different from regular squats and doesn’t reflect the mechanics of how we squat in everyday life (e.g. raising off a chair). The machine forces your torso upright, which means you lose your neutral spine and can suffer increased load on your low back. This squat also biases your quads instead of your posterior chain (glutes, hamstrings), which is what, ideally, should be very active throughout a proper squat.

Worst: There is Such Thing as Perfect Form

Fitness professionals and gym junkies alike are most comfortable when an exercise has a perfect form or technique associated with it. This paint-by-numbers approach makes it easier to critique others’ squat form by running through a mental checklist. While there is definitely ideal form and bad form, there is no perfect form because it is relative to everyone’s unique body structure, fitness, and level of body awareness. This means that the best squat form can vary slightly from person to person.

In reality, the amount of pelvic tilt, squat depth, and forward lean can be dictated by the ratio of the individual’s limb to torso length, hip socket anatomy, and other unique musculoskeletal variations. It is better to think of the ideal squat form as being something that prevents injury, respects the individual’s training and structural limitations, is efficient, and can be duplicated over time without pain.

Best: Wear Flat Shoes

Thick soled, heavily cushioned running shoes might be great for walking, jogging, or other sports, but they are not ideal for squatting in. In fact, for many exercises, including squatting, minimum soled, flat shoes are best. This is because running shoes usually have a higher heel and this makes you more likely to lean forward with your weight. Additionally, shoes with motion control can restrict your ankle from moving freely throughout the movement and won’t help to build the stabilizing muscles in your feet.

When squatting, a flat foot with most of your weight in your heels reduces the load on your knees and help activates your posterior chain (glutes, hamstrings, and core muscles). Look for shoes that are relatively light and flat, or at least ones that have minimum lift through the heel. Another alternative is to squat barefoot (or in socks), however this might not offer enough support for most people.

Best: Stay Tight

When you hear the word squat, there is a good chance you describe it as a lower body exercise that works your quads, glutes, and hamstrings. True, the squat does demand a lot of these muscles but the movement is much more than that—it is a fully body movement. Consider how tightly you need to grip the bar, taut across your shoulder blades, and the tension you need to generate through your core.

Instead of focusing too much on a single cue, such as pushing your bum back, pushing your core down and out, or tightening your shoulder blades, think about the big picture. In this case, the big picture is the tightness you create throughout your body to resist undesired movement (e.g., flexing your spine or knees caving in) by being one, strong unit in lowering yourself into and raising yourself out of a squat.

Best: Spread the Floor

Have you ever watched someone else squat, notice their knees cave in, and wince? If you have, you’ve done so for good reason—allowing the knees to cave in places stress on the joint and paves the path for future injury. A cue made popular by powerlifters to prevent the knees from caving in is to ‘spread the floor’. This is a technique you can try standing, with your knees slightly bent.

To execute this, imagine the floor beneath you could be separated into two pieces, one under each foot. Keeping your feet flat on the floor, try to spread the floor apart by keeping your feet in place and your knees over your second toe. This helps increase the activation of your abductor muscles in your hips which then stabilize the knee. You can also loop a light resistance band above your knees and think about pushing against the band while squatting.

Best: Perform Accessory Moves

One of the best ways you can improve your squat has nothing to do with squatting at all. Working on accessory moves that target weaker muscles and motor patterns translates into improved strength, coordination, and muscle firing in your regular squatting. To target the glutes, try doing single leg glute bridges, single leg hip thrusts, side lunges, lateral step-ups, or cable hip abduction. It is very common to have one glute that is stronger than the other, which is why single leg work is your best bet.

For the quads, single leg work—such as stationary or walking lunges, split squats, and traditional single leg squats help improve coordination and decrease muscular imbalances from one side to the other. Hamstring work can include good mornings, Romanian deadlifts, straight leg cable kickback, hamstring curls with the stability ball, and the hamstring curl machine.

Best: Pay Attention to Lateral Shifting

For some reason, little attention is given to avoiding and addressing any significant laterals shifting throughout the movement. Videotape yourself or watch a friend squatting from behind using a barbell. Observe the movement of the bar throughout the exercise—does it seem to tilt up or down on side? Take a closer look at the bottom of the squat, is there a quick shift to one side?

Slight movement to one side is okay, but major shifting or bar tilting isn’t. This usually indicates a muscular imbalance, restricted joints or muscles, a motor pattern problem, or all of these issues. If you continue squatting like this, you will over work certain areas of your body, which will lead to pain and injury. Your best bet is to be assessed by a physiotherapist to identify where the problem is coming from and what you can to do fix it.

Best: Listen to Your Body

When you participate in an exercise program that calls for a certain amount of sets, reps, and frequency of squatting per week, it can be tempting to show up and squat regardless of how you are feeling. Although it is normal to need a bit of motivation or a pep talk before performing a challenging exercise, knowing when you should and shouldn’t push through your slump is imperative.

If you are experiencing discomfort in any of your joints or muscle pain that extends beyond regular exercise soreness, skip the squat and try an accessory movement instead as long as they don’t bother you. Squatting through an achy joint or pulled muscle is counterproductive and can lead to a longer-term hindrance of reaching your goals. If you are extremely fatigued, you are less likely to be able to maintain good form and should skip squatting that day.